It’s Friday night in our summer school which means it’s disco night! The disco is always a crowd-pleaser and there’s never a reason to offer alternative activities to cater to those who fancy doing something else. The footballs and volleyballs can have a rest for at least one evening.

This summer we insisted on ‘English only’ discos. A carefully selected and approved song list, no foreign language song requests mid-disco, and unfortunately, no Macarena. If you’re raising an eyebrow at this, just hang on – there are good reasons.

Before deliberating on the, ‘why’, I should first acknowledge that the ‘English only for everything’ in a summer school environment is both impractical and undesirable, whether that is inside the classroom or beyond. In most circumstances, allowing a learner’s L1 and encouraging them to bring their own culture into the environment is not only normal but potentially beneficial.

Language acquisition probably requires all the linguistic resources we have. I no longer believe in the English only learning environment, whether in the classroom or out. In fact, I don’t think I ever really believed in it. Anyone who tells you they manage to do it is fibbing and quite frankly, it’s probably not a desirable condition for language acquisition. Ideas around translanguaging inform us that learners have a singular repertoire and not compartmentalised language resources which are code-switched (Wei, 2018). We empower learners by drawing on all linguistic resources to scaffold understanding and aid acquisition.

Learning occurs outside the classroom as well as in it. Within the summer school environment, the language students get to practise and acquire doesn’t just stop at the classroom door; the entire context is a learning environment. The prevailing practice of, ‘we only speak English in lessons’ is rarely stretched to activities outside the classroom. If it’s sound pedagogic practice, why not apply it more broadly? We allow students to use their L1, translate messages, and bring cultural elements into the mix, but when it comes to lessons, these are mostly left outside the classroom- although they still gate crash even if they’re not invited.

Learning does not just take place in the classroom and as a lot of what our learners acquire is incidental and based on real world needs…

You’re a language student…

You’re in a shopping centre with your group. You turn your back for one second and they’ve all disappeared. You’re now lost and must cobble together enough language to ask the security guard for help.

You’re not feeling well and need to explain your symptoms to the Welfare Manager in the school to get help.

You want to gather other students to play a game of football. This requires organisation.

Etc.

We all have cultural identities which make us who we are. Bringing cultural elements into the summer school space helps us form bonds. Nobody is an empty vessel, devoid of culture and lived experiences. Food, music, dance, traditional games – these are part of all of us and cannot be separated from who we are. These things validate our identities and allow everyone to be seen and respected. They help create meaningful connections between disparate cultures which would otherwise be distant. As young fella myself, I loved to meet and talk with people from places I’d never heard of: Is it cold? What are the people like? What food do you eat? What music do you listen to? What language do you speak? How do you say, ‘hello’… To the inquisitive mind, this really is a small pleasure and made even more enjoyable when the conversation is reciprocated. Meaningful, real-world communication, all wrapped up in a target language tortilla.

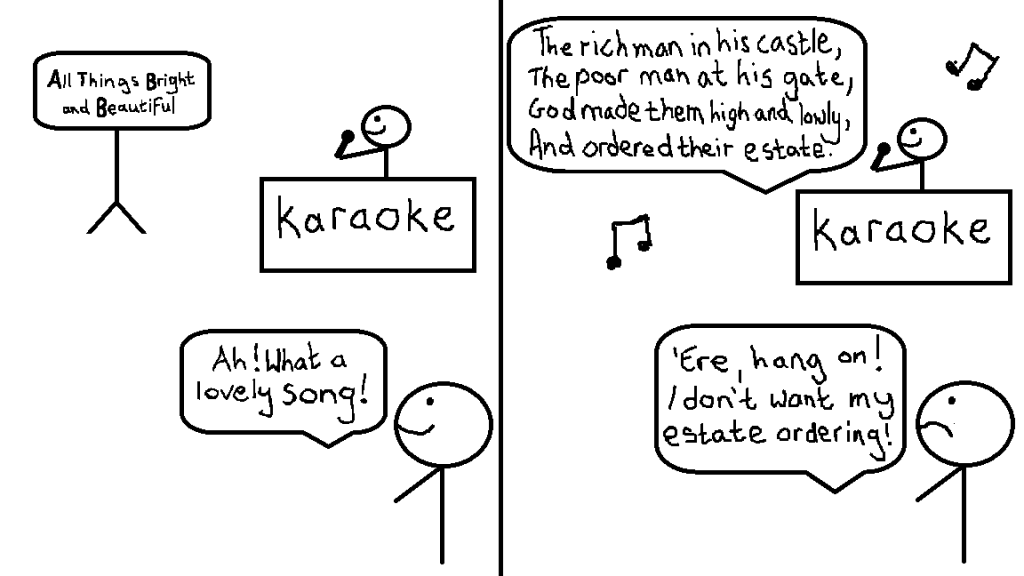

The above forms a reasoned argument as to why we should be inclusive of more than just the language we wish to acquire. Backtracking from this position may see a non-sequitur but for the purposes of a specific situation in a unique environment, here are some reason why we probably should be somewhat mindful of the music we play at a summer school student disco or karaoke:

- Safeguarding – if we can’t understand what is being said, we are unable to ensure the content is appropriate. It sounds obvious but unless you’re a polyglot, you really can’t know if that song request is about flowers or something utterly horrendous.

- Conflict – we cannot be aware of every global conflict. Sabre-rattling nation states, timeworn hostilities in far-flung places – what about that song request which turns out to be a Trojan Horse of jingoism and assorted bluster? The request may well be innocent: the sentiment may well be missed by those who made the request – don’t once sensitive themes become palatable in society once they have been mainstreamed? However, regardless to how deeply codified and canonised taboo concepts become, they won’t be missed by those who feel they are on the receiving end of the message.

- Fairness – The disappointed students who tells us that everyone else got to play their music, but what happened to the song request from their country? Better luck next week, eh? But how does this student go away feeling? Marginalised? Excluded? Ignored? If everyone else gets to share their music, it should be an equal venture. If you have diverse nationality/ linguistic groups at your disco, it’s going to be difficult to cater to all.

- Universality – English language music is ubiquitous and popular enough to keep everyone happy. A lively disco is a successful disco and invariably, people will only dance to the songs they know. When that popular song in (pick a language), which everyone knows (in that country), gets played, everyone not from (that country again) will sit down if they don’t know it.

So how did we sell this as a concept? It’s an English language summer school so we’ll only play music in English! Simple, not especially unjustified, and doesn’t necessitate further explanation.

How did it work in practice this summer? It worked well with a carefully crafted song list. It’s as simple as that. The parameters were set in advance: no foreign language song requests and any English language requests needed a cursory check for appropriacy prior to being played.

However, it’s worth pointing out a couple of instances when it did not work.

During the first disco this summer, the resident DJ caved in to requests and before he knew it, he was playing a pile of popular tracks from around the world. Everyone was aware from the start this was an English only disco and when all bets were off, it led to complaints from those who didn’t get to play their songs. Worse still, there was a suggestion of favouritism towards songs from specific countries/ language groups.

The last disco of the season struggled to get up to speed. This was not surprising given how tired everyone was and with student numbers being in double rather than treble figures, it was a bit of a slog to get everyone motivated. The team on the ground had an idea, they changed tack and decided to get different nationality groups to teach everyone a dance from their country. The concept garnered some traction but not before a specific nationality group made it abundantly clear they were not happy and wouldn’t be staying any longer at the disco.

To say they were not happy was an understatement and by the time the message had landed on my desk, we were accused of being insensitive. The reason? A long and sustained bloody conflict in their region which gets very little attention outside of its immediate proximity. Of course, the information is there but you would need to dig a little to get it; assuming you don’t know already.

Hostilities we were not aware of brought to a head by our actions. Crying students, angry Group Leaders, and some red-faced and very sorry staff members, we were able to resolve the issue once everyone had a moment to breathe. Here’s the truth of the matter: although the action was interpreted badly, the intention was not to offend. Fundamentally though, it could have all been avoided had they just kept the music to English. They could have kept the dancing though… Maybe rounded it off with some something traditional. Anyone for Morris dancing?

Reference: Wei, L. (2018). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics, Volume 39, Issue 1, February 2018, Pages 9-30. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx039

Want to support this channel? You could buy me a coffee!

Interested in summer school related tools and topics? Click here: Summer school ideas.

More about translanguaging? Click here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Translanguaging and here: https://ealjournal.org/2016/07/26/what-is-translanguaging